The Future of General Systems

One sees more references to complex systems now than general system(s) theory. Institutes of Complex Systems provide a home base for scientists and scholars who continue cross-disciplinary studies in the spirit of Bertalanffy and Rapoport.

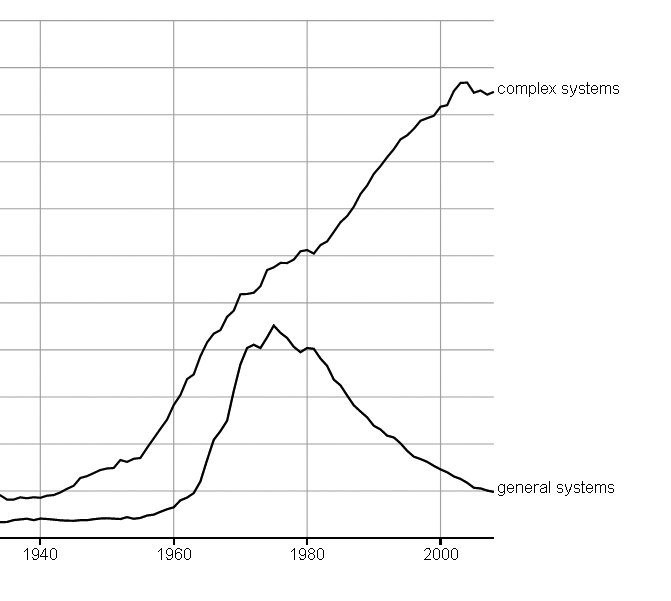

The shift in popularity from general systems to complex systems is visible in Google's ngram viewer. The ngram viewer is a free service that displays frequency of word usage in English language literature scanned by Google.

References to "complex systems" have far surpassed references to "general systems."

References to general systems peaked in 1974 then declined. The same is true of references to "Bertalanffy" and "Anatol Rapoport" and "general system theory." All peaked around the same time, from 1969 (Rapoport) to 1974 (general system theory).

References to "complex systems" tracked upward together with "general systems" until 1974 when the two began to diverge. General Systems fell in usage but references to complex systems continued to rise into the 21st Century.

Organizations and conferences devoted to General Systems still exist, but they do not receive much attention from scientists. By contrast, over 100 institutes devoted to Complex Systems have sprung up around the world, many within the past ten years.

Here is a sampling, along with introductions from their websites:

- The Institute of Complex Systems (ICS) is in Jülich, Germany. ICS is devoted to the "continuing transfer of techniques, methods, concepts and materials" between disciplines such as "physics, chemistry and biology."

- The New England Complex Systems Institute (NECSI) is in Cambridge, MA. "We study how interactions within a system lead to its behavioral patterns, and how the system interacts with its environment... NECSI's unified mathematically-based approach transcends the boundaries of physical, biological and social sciences, as well as engineering, management, and medicine."

- The Northwestern Institute on Complex Systems (NICO) is in Evanston, IL. "The Northwestern Institute on Complex Systems was founded in 2004 with the goals of uncovering fundamental principles governing complex systems... NICO brings together faculty in business, engineering, education, medicine, natural sciences, and social sciences..."

- The Santa Fe Institute is in Santa Fe, New Mexico. "The Santa Fe Institute is the world headquarters for complexity science... Our researchers endeavor to understand and unify the underlying, shared patterns in complex physical, biological, social, cultural, technological, and even possible astrobiological worlds."

- The Institute of Complex Systems Simulation (ICSS) is at the University of Southampton in Southhampton, UK. "The Southampton Institute for Complex Systems Simulation (ICSS) provides a stimulating home for interdisciplinary research that combines complex systems ideas and tools with computational methods in order to address challenges within key application domains spanning climate, pharma, biosciences, nanoscience, medical and chemical systems, transport, the environment, engineering & computing."

- The Complex Systems Institute (CSI) is at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte in Charlotte, NC. "Tools developed by CSI members help analysts model infrastructure and social networks, visualize and understand how individual networks behave, and understand multiple-network interdependency behavior..."

That is only a few of more than 100 institutes now devoted to the study of complex systems. Non-English-language sites include the Institute for Complex Systems (CNR-ISC) in Rome, Italy, which was the source of the research about flocks of birds turning in a way that resembled liquid helium.

One answer to the question, "What is the future of general systems?" appears to be, "Its spirit continues in institutes for the study of complex systems." Almost all are affiliated with major universities.

None of these institutes explicitly cites Bertalanffy or mentions General Systems. All of them are devoted to cross-disciplinary studies in search of principles, findings, and mathematical models useful for analyzing a range of systems. That is what Bertalanffy, Rapoport, and others set out to do.

For intermediate students interested in complex systems, one of the best places to go is the complexity explorer web site sponsored by the Santa Fe Institute. It is devoted to listing "online courses and other educational materials related to complex systems science" including the excellent, free MOOCs (online courses) offered by Santa Fe Institute staff.

Is it Really About Complexity?

Ironically, complexity (as such) was never mentioned by the founders of General Systems. Locating interdisciplinary and cross-situational patterns, principles, laws, and formulas was at the heart of the matter for them, whether systems were simple or complex.

Complexity was also not a key focus of this toolkit. Most of the principles are simple, focusing on patterns students might understand immediately with a few examples.

By contrast, the typical Institute for Complexity Studies is intended for PhD students and postdocs and career scientists. The publications and research projects emanating from these institutes justify "complexity" as part of the name.

I tend to think, however, this complexity is a side-effect of being on the cutting edge of science. The simplest systems yielded to scientific understanding long ago.

When I found out the Santa Fe Institute was offering a MOOC on Complex Systems in Spring, 2013, I signed up for it. This was my first experience as a student after teaching for 30 years, and it was fun.

The course was taught by Melanie Mitchell, whose 2010 book Complexity: A Guided Tour was much like the course. It is a good book to read, for students interested in the next step up in complexity from this toolkit.

Melanie discussed the issue of how to define complexity in her first unit. She included video interviews with several other luminaries from the Santa Fe Institute, regarding various definitions of complexity.

This revealed that the issue of how to define complexity is not settled. That was Dr. Mitchell's opinion as well.

Several operational definitions of complexity are available. Most relate complexity to the length or difficulty of descriptions of a system, which might include the number of interacting agents in a system, the non-linearity of its behavior, or the non-uniformity of its structure, its unpredictability, or the amount of computing power require to characterize the system.

Meanwhile, subjects covered under the label of Complex Systems are often about simplification. They show how apparently-complex systems can be generated by iterative processes. For example:

- Fractal construction principles show how large, complicated-looking structures are produced by repeating simple routines.

- Stephen Wolfram's cellular automata reduces complex computing to simple iterative processes.

- The Logistic Map shows how complex, chaotic behavior can arise from simple dynamical equations

See a pattern there? It almost invites a general system principle: "Wherever you see a Complex Systems demonstration, you will find some complicated thing arising from iterations and combinations of much simpler processes."

Studies of complex systems are not about celebrating or multiplying complexities. They are about detecting simplifying principles that underlie apparent complexity.

The label complex systems is now locked into the titles of institutions all over the world and will not change. But complexity is not the focus, goal, or desirable outcome of complexity studies. The goal is to explain complex-looking systems, using clear and simple principles.

The more simpler and clear a rule or algorithm, the more it seems elegant. A great example comes from Anatol Rapoport. In 1979 Rapoport entered a game theory competition sponsored by Robert Axelrod, based on the Prisoner's Dilemma game.

Prisoner's Dilemma was a game invented at Princeton's Institute for Advanced Studies in the 1950s. Trust and betrayal are the two main options.

The tournament played computer against computer, and Rapoport's entry won first prize, yet it only required 4 lines of code (5 in Fortran). The strategy of Rapoport's program was tit-for-tat. There were two rules:

Cooperate on the first round.

On round t>1, do what your opponent did on round t-1.

The importance of this finding is hard to overstate. Prisoner's Dilemma captures the essence of conflicts between hostile parties. If tit-for-tat is the best overall solution, that has implications for how to do effective diplomacy.

If you were at an Institute for Complex Systems, would a solution like tit-for-tat put you out of business? Not at all. Once you have a good tool, you move on to the next level of complexity, studying when and how best to use it.

If you were a PhD student with a special interest in conflict resolution, you might study how the tit-for-tat strategy has been used or misused in the past. When has worked or not worked, and why?

How might it be applied in the Middle East, or on the Korean peninsula, or in other political hot spots? A simple tool can be employed to ask and answer complex questions.

Much of the work going under the name of Complex Systems has this characteristic of intent to simplify. Principles such as synchronization, scaling, and the variation-with-selective-retention pattern in creativity greatly simplify the analysis of complex systems.

Easy and Obvious

Tools, including cognitive tools, do not become obsolete because one gains expertise with them. That is when they are at their most useful.

However, frequently used cognitive tools may become implicit, called upon without being called out. Habits of thought become familiar until one is hardly aware of using them.

Any tool that is used repeatedly tends to be like this. For those who already find the General Systems principles in this toolkit easy and obvious, good! Your cognitive toolkit is well stocked, and you are ready for greater challenges.

Write to Dr. Dewey at psywww@gmail.com.

Search Psych Web including the General Systems Toolkit and the online textbook Psychology: An Introduction below.

Copyright © 2017 Russ Dewey