| Name |

Stimulus |

Response (output) |

| Gag reflex | Throat obstruction | Gagging, vomiting |

| Tear reflex | Eye irritation | Tears |

| Startle reflex | Loud noise | Head, arms. Body, eyes move |

| Patellar reflex | Tap tendon below knee | Lower leg jerks |

| Salivary reflex | Food in mouth | Saliva in mouth |

| Orgasm | Sexual stimulation | Pleasure, glandular and muscular responses |

| Letting down | Baby at breast | Milk released |

| Pupillary reflex | Light | Pupil contracts |

Classical Conditioning

Classical conditioning is the most primitive and basic form of learning. It occurs even in animals with very rudimentary nervous systems, like the Aplysia or sea slug, a fist-sized invertebrate shown below.

An Aplysia, courtesy of Tom Capo of the University of Miami

Despite the simplicity of classical conditioning, beginning students often emerge from a unit on classical conditioning with a remarkably fuzzy understanding of it. Perhaps the antique terminology is at fault.

Students' eyes glaze over when confronted with terms like conditional stimulus, unconditional stimulus, unconditional response, and conditional response. However, we are stuck with these labels from 1900.

For now, concentrate on understanding classical conditioning on an intuitive level. You can learn the labels when you have a basic understanding of classical conditioning, and that will make them easier to understand and remember.

Classical conditioning: What is it?

Classical conditioning is a very simple form of learning. It must be, if a sea slug can do it. Classical conditioning occurs when animals learn that a stimulus predicts some biologically significant event such as the appearance of food.

After a stimulus (such as odor) precedes a biologically significant event (such as the availability of food) animals learn the connection. The next time the stimulus occurs, the animal acts like it expects the same event to follow.

Thus a classically conditioned response is an anticipatory response. If the animal is an Aplysia, and it expects food, it extends its feeding tube.

What is a three word summary of classical conditioning?

Classical conditioning is simple, but it was a major advance for creatures on Earth. In its own humble way it is a prediction of the future.

The sea slug senses the odor of food. It extends its feeding tube even before food is encountered.

This enables the sea slug to feed quickly and consume more food than competitors who wait until they bump into food before responding to it. The smarter sea slug reproduces more, and its descendents take over the seas.

How might a sea slug gain an advantage by making a response early?

Classical conditioning occurred in simple animals, and continues to occur in humans, because any animal can benefit from making anticipatory reactions. All animals need to prepare for the future.

Creatures like the sea slug follow the simplest rule: "If it happened before, it may happen again." After A is paired with B a few times, A is treated as though it predicts B.

Because this is so simple and basic, classical conditioning does not require conscious thinking or language. It can influence people (or sea slugs) without a conscious thought process.

We hinted at this in Chapter 3 (States of Consciousness) when discussing two modes of thought in human mental life. Different labels are used to describe the two modes: serial vs. parallel processing, intellectual vs. emotional processing, head vs. heart, or analytic vs. intuitive thought.

How does classical conditioning relate to the "head vs. heart" distinction discussed in Chapter 3?

Often these pairs correspond to conscious vs. unconscious thought processes. Classical conditioning comes down on the "parallel, emotional, heart, intuitive, unconscious" side. The effects of classical conditioning are automatic, not requiring attention.

Reflexes

In the 1800s, scientists knew little about the nervous system. They knew the body had nerves. They knew the nerves were involved in reflexes that were input/output circuits built into the nervous system.

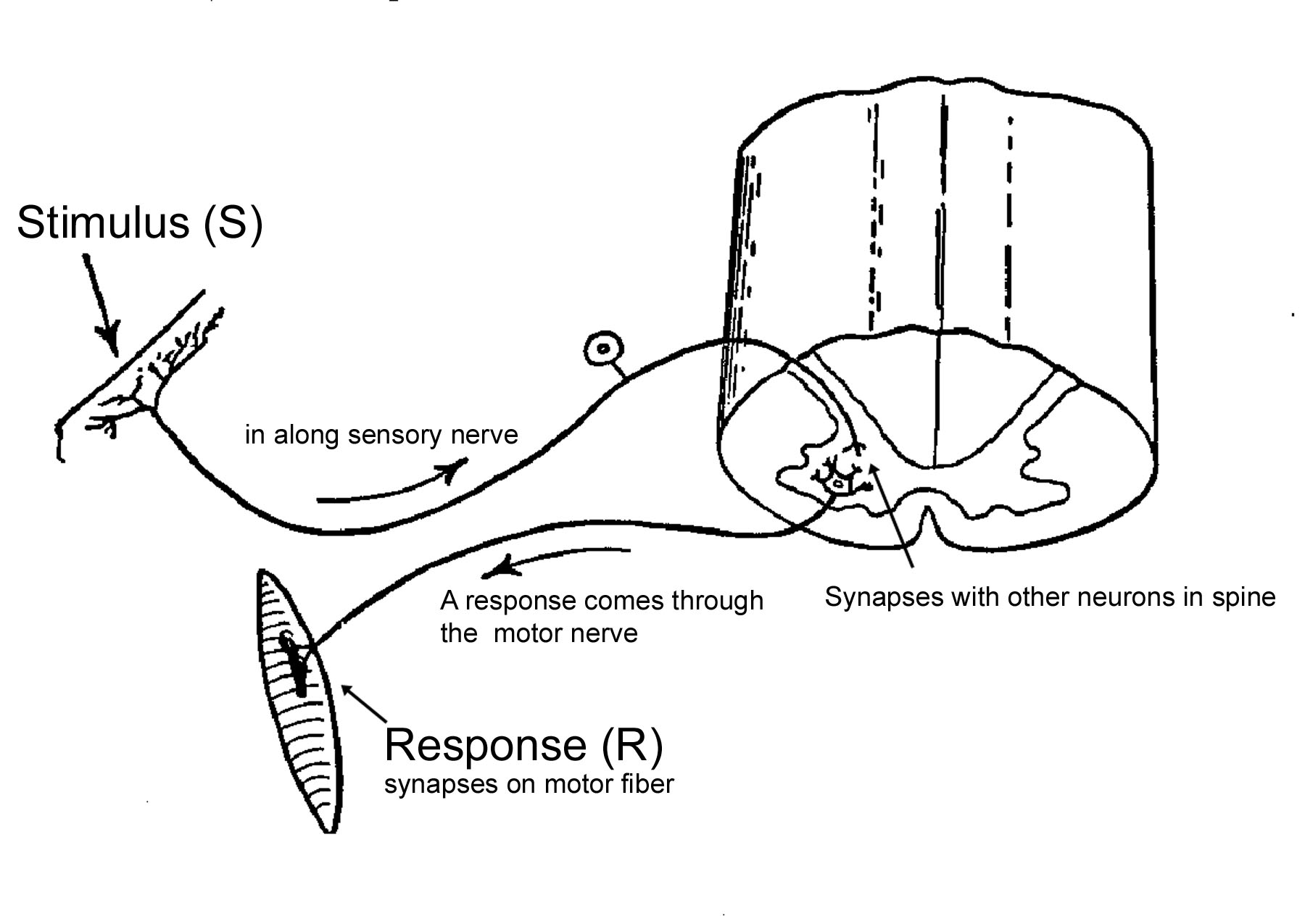

In a reflex, some stimulus (an input to the nervous system) produces a response (an output from the nervous system). Here is a classic diagram of a spinal motor reflex from the 1920s. It shows the essential elements.

In a reflex, there is a sensory component (stimulus) and a motor component (response).

What components are found in all reflexes?

All reflexes have a stimulus component and a response component, corresponding to sensory and motor neurons, respectively. The simplest examples are spinal motor reflexes such as the knee jerk reflex (patellar reflex) or the finger withdrawal reflex.

In the knee jerk reflex, a stimulus to the patellar tendon, below the kneecap, stimulates sensory neurons to send signals to the spine. In the spine, axons from the sensory neurons synapse on the dendrites of motor neurons, triggering nerve impulses that are sent back out to muscle fibers, making the leg jerk.

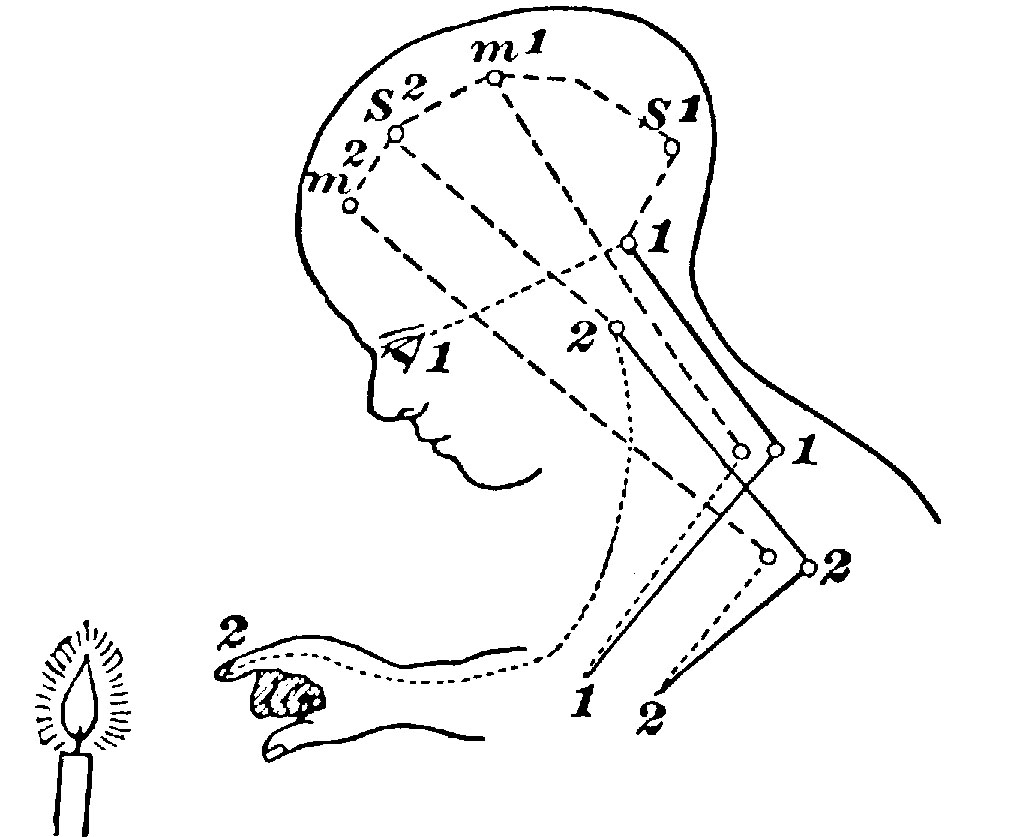

In the finger withdrawal reflex, pain causes the finger to be withdrawn. The following figure, from the frontispiece of William James's Psychology: The Briefer Course (1892), shows the 1890s conception of neural circuitry underlying the finger withdrawal reflex.

The finger-withdrawal reflex as depicted by William James in 1892. Inputs go through the sensory nerves (1 and S) and responses come out the motor nerves (M and 2).

The following table lists some reflexes in humans. In each case a stimulus activates sensory neurons, triggering motor responses. The response is always biologically significant, helping to preserve the individual and the species.

What are some examples of reflexes in humans?

Reflexes are stereotyped in form. They are present in all normal members of a species. They are built in and do not need to be learned.

For example, snakes are born with all the reflexes they need. They emerge from an egg and slither away to hunt without any learning.

The word reflex had a broader meaning in the late 1800s when Pavlov used the term. In those days the word reflex was used to describe almost any biologically based behavior. Russian psychologists called themselves reflexologists from the 1880s through about the 1920s.

What did the word "reflex" mean to Pavlov and other Russian scientists?

Human beings are obviously influenced to a very great extent by learning. How could reflexes, patterns fixed into place by biology, be the building blocks of human behavior?

The missing link was provided by Pavlov. He showed that reflexes could be modified by learning. In particular, they are set off by a stimulus the animal learns to associate with activation of the reflex.

Pavlov's Dog

Ivan Pavlov was one of the most prominent scientists in the world at the beginning of the 20th Century. His discovery of classical conditioning came late in his career.

For decades, Pavlov did research on digestive reflexes. He studied how food delivered to the stomach triggered the processes of digestion. He was an exceptionally good researcher who received a Nobel Prize for his research.

When Pavlov delivered his acceptance speech at the Nobel Prize banquet in 1904, he surprised the crowd. He lectured about something he discovered accidentally while doing his digestion research.

Why was Pavlov awarded a Nobel Prize? How did he surprise the audience?

Pavlov announced that he had discovered conditional reflexes. These were reflex-like responses that were contingent upon early learning.

Pavlov giving his Nobel Prize speech in 1904.

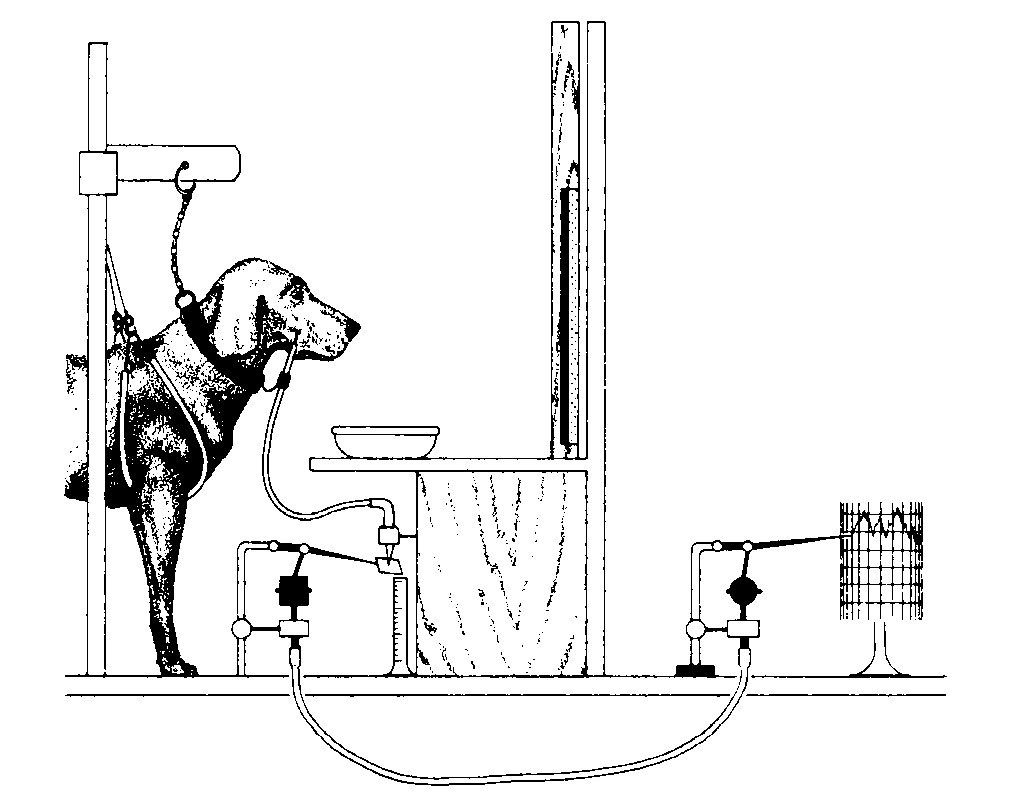

The discovery occurred when Pavlov connected a clear tube to the dog's salivary gland in the cheek. He did this to measure the amount of salivation that took place after food was placed in the mouth. The set-up of Pavlov's co-worker G.F. Nicolai is shown below.

A dog with a tube connected to its salivary gland

The dog was restrained in a harness with its head held still, so the tube would not rip out. The researcher puffed meat powder into the dog's mouth to start the digestive process.

As you probably know, dogs salivate ("slobber") when they eat. When meat powder entered the dog's mouth, that stimulated lots of saliva, which dripped out of the tube into a beaker where it could be measured.

With a set-up like this, Pavlov probably could not help but notice that dogs anticipated their meals. When a researcher entered the laboratory carrying meat powder, saliva began dripping out of the tube.

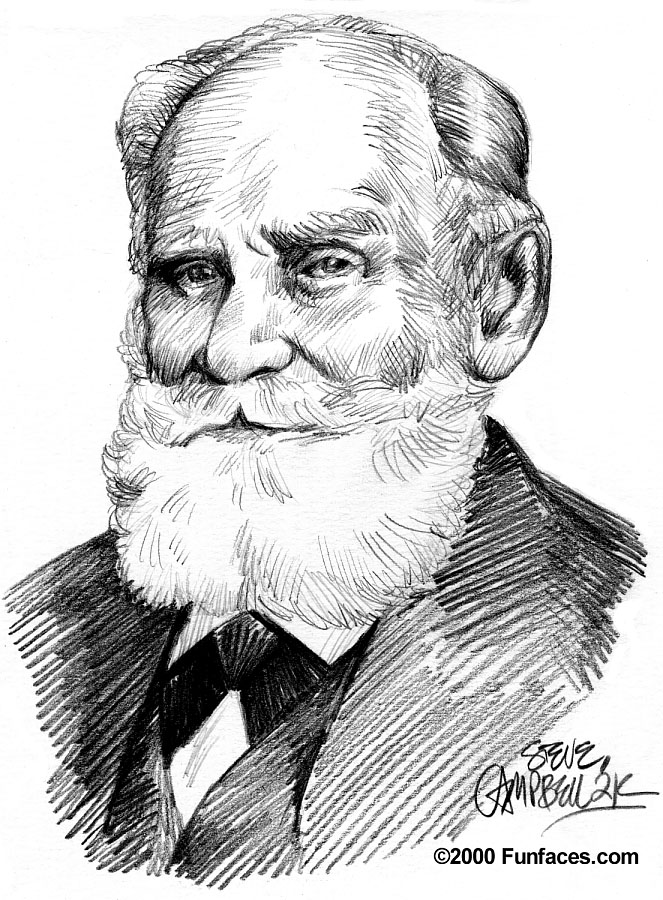

Ivan Pavlov

Pavlov realized this was significant. A biological reflex (salivation) was being modified by something psychological, namely, anticipation.

In Pavlov's terminology, the dog's prediction was a form of "psychic stimulation" that activated the reflex. How could this happen? Reflexes were biological, yet the reflex was influenced by a psychological stimulus: the expectation of food.

In what sense did Pavlov's dog respond to a psychological stimulation?

Pavlov next devised a systematic version of his accidental observation. He (1) sounded a tone, and then (2) fed the dog meat powder. After a few repetitions, the dog started salivating when it heard the tone, even before the meat powder entered its mouth.

Pavlov was in his late 40s when he discovered this. He changed his research program to focus on this phenomenon, and he continued studying it until shortly before his death at age 87.

In 1906 Pavlov followed up on his Nobel Prize speech by submitting an article in the American journal Science, summarizing his findings. The article was titled, "The Scientific Investigation of the Psychical Faculties or Processes in the Higher Animals." In those days, psychical meant the same thing as psychological.

Pavlov had a one-word label for classical conditioning. He called it signalization. That is not a bad label for classical conditioning. It occurs when a signal triggers a reflex-like response.

What was Pavlov's one-word label for classical conditioning?

In America, John B. Watson (the "father of behaviorism" described in Chapter 1), heard about Pavlov's research. Watson decided to use Pavlovian conditioning in his own research.

Watson carried out studies of the fingertip withdrawal reflex. Watson would ring a bell then quickly shock a person's fingertip with a small amount of electricity, causing involuntary withdrawal of the fingertip. Soon the person would withdraw the fingertip when the bell rang.

How did Watson use Pavlov's method?

Pavlov's dog and Watson's fingertip illustrate the basic pattern found in all classical conditioning. An organism learns that a signal predicts the activation of a reflex. After learning this, the organism reacts to the signal with an anticipatory response similar to the reflex response

Write to Dr. Dewey at psywww@gmail.com.

Don't see what you need? Psych Web has over 1,000 pages, so it may be elsewhere on the site. Do a site-specific Google search using the box below.

Copyright © 2007-2018 Russ Dewey