Copyright © 2007-2018 Russ Dewey

The Contributions of Konrad Lorenz

Many of the basic ethological concepts we reviewed on the previous page came from Nico Tinbergen. Tinbergen's friend and associate (and fellow Nobel Prize winner) Konrad Lorenz was equally if not more influential.

On this page we will look at foundational concepts of ethology that Lorenz invented or publicized. Often he did research on a species he knew and loved, the graylag goose.

In another parallel with Nico Tinbergen (who had played with sticklebacks as a child) Konrad Lorenz grew up around the graylag goose. It is a native of northern and central Eurasia, domesticated and raised for meat for over 1,000 years, found on many farms.

The Greylag Goose

The greylag goose retrieving its egg

The example above is found in so many animal behavior textbooks it might be called the Pavlov's Dog of ethology. This is the greylag goose retrieving her egg.

Lorenz and Tinbergen wrote an article about this fixed action pattern in 1938. They used it as a paradigmatic example of instinctive behavior, set off by a specific stimulus.

How does the greylag goose retrieve her egg?

The sight of an egg outside of the nest sets off egg-retrieval. When a human puts an egg near the nest, the greylag goose sees it but does not immediately reach for it. She does a "double take." She looks away from it and then looks back.

Next she moves her head back and forth toward the egg in several short, quick movements. Then she extends her neck as far as it will go (quite far, in a goose) and moves toward the egg with her neck fully extended, using a curious low-to-the-ground waddle unique to this situation.

"When the bottom of her beak touches the egg, the goose's neck muscles quiver with tension and slowly she contracts her neck, rolling the egg back toward the nest. The egg (being egg shaped) tends to roll off to one side or another.

"The goose moves her beak from side to side, keeping the errant egg on course. If it eludes her, she returns to the nest, spots the egg still lying outside the nest, and repeats the whole movement." (Bermant and Alcock, 1973)

What is endogenous running-out?

Lorenz found that if he removed the egg while the mother bird reached for it, the bird nevertheless went through the whole action of retrieving the egg, as if retrieving an imaginary egg. This led Lorenz to formulate the concept of endogenous running-out.

Endogenous means coming from within. Once the action pattern was set off by a sign stimulus, the motor program kept running to its conclusion, even if the egg had rolled off to the side.

Manning (1972) pointed out that reflexes are good examples of motor programs or action patterns. They are species typical, fixed in form, and they show endogenous running out.

In humans, vomiting illustrates the all-or-none character that Lorenz labeled endogenous running-out. One can hold it off for a while, but once it starts, it must be carried through to completion. Many but not all action patterns have this characteristic.

Supernormal Stimuli

A bird tries to retrieve an abnormally large egg while ignoring realistic eggs

Lorenz once put a football-sized model egg by the nest of a bird. The bird tried to retrieve it using the same action pattern it would use for a normal egg.

If a normal egg was placed alongside the giant one, the bird made fruitless attempts to retrieve the big egg while neglecting its own normal-sized egg.

Lorenz called the exaggerated sign stimulus a supernormal stimulus. Supernormal sign stimuli are bigger or more intense than normal. They elicit a larger-than-normal response from the animal.

What is a supernormal stimulus?

Why would a bird prefer a grotesquely large egg to a natural one? Manning (1972) speculated that larger eggs are usually healthier.

Giant eggs never occur in nature, so there is no need for an upper limit on the animal's preference for larger eggs. (Actually, there is some upper limit. A bird would not attempt to retrieve a house-sized egg.)

How might facial make-up be a supernormal stimulus for humans?

Do humans respond to supernormal stimuli? Perhaps. Humans have a natural response to the features of human faces. Cosmetics exaggerate those features, creating supernormal stimuli.

Rouge exaggerates rosy cheeks; lipstick exaggerates red lips; eyebrow pencil and eyeliner exaggerate the darkness of eyes; false eyelashes exaggerate eyelashes. A made-up face may elicit a larger than normal response.

Imprinting

When Konrad Lorenz lived on a farm with greylag geese, he noticed that young goslings followed the first thing they saw after hatching. Lorenz called this phenomenon imprinting.

In normal circumstances, this works our for the birds because the first thing they see is the mother goose. However, if a gosling sees a human first, they follow the human as if it were mother.

In a famous picture on the cover of Life magazine, Lorenz was shown walking on his farm with a string of goslings following him. The Saturday Evening Post responded with a picture by the artist Norman Rockwell, showing ducklings following a football.

What is imprinting? With what animals is imprinting common?

Ducklings will also imprint on the first thing that moves, when they hatch, whether it is animate or inanimate. Imprinting is found mostly in ground dwelling birds and prey species such as goats and lambs. It keeps the young in close proximity to a protective parent.

Ground-dwelling birds sometimes imprint on the first moving object they see.

Ground-dwelling birds sometimes imprint on the first moving object they see.

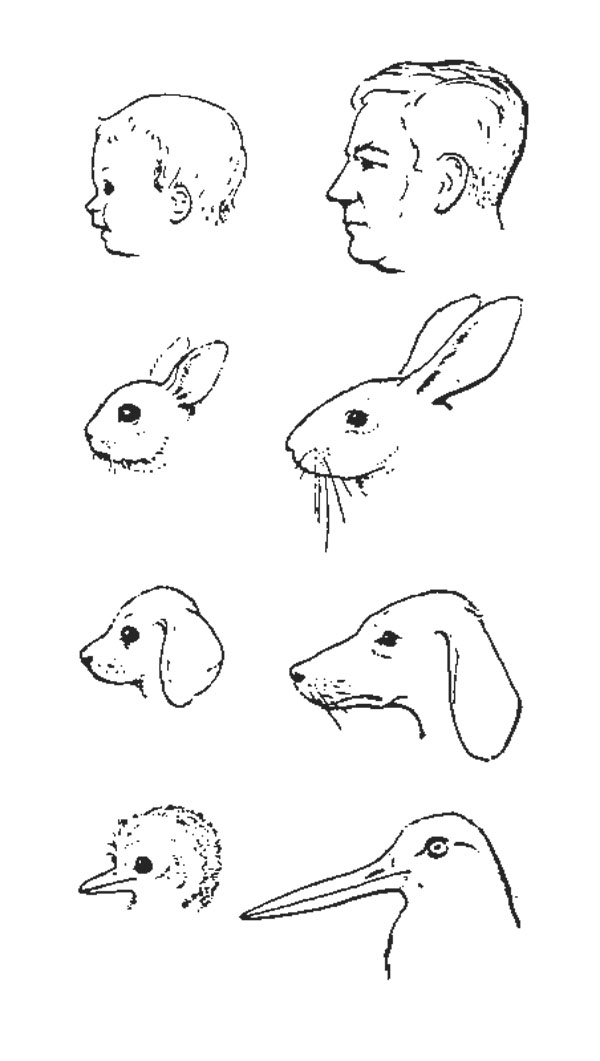

Babyishness

Lorenz noticed that baby animals of many species have the same look. For one thing, they have large heads in proportion to their bodies.

"Babyishness" in different species

They have large, round eyes, protruding foreheads, soft jaw lines and plump cheeks. Often they are fuzzy, and they have stubby legs.

Lorenz labeled this pattern of features babyishness. He pointed out that we respond to these features with affection and good humor, labeling them as cute, whether they appear in human babies, other species, stuffed animals, or cartoon characters.

What is the "babyishness" pattern noticed by Lorenz?

Stephen Jay Gould (1979) perceived an evolution toward babyishness in the features of Mickey Mouse. When Disney first drew Mickey for Steamboat Willy (1928) Mickey's snout was long, his forehead was small, and his behavior was rather aggressive. Mickey created music on the steamboat by pulling tails and otherwise torturing various animals, making them cry out.

By the 1950s, Mickey's behavior had mellowed and his appearance had become more babylike. His ears were moved back on his head (creating a larger cranium).

Mickey's eyes were enlarged by making the former eye into a pupil in the new eye. His snout became shorter and upturned, less rat-like. He was given trousers, which made his legs look stubby. In many ways, Mickey became babyish and therefore cuter and more lovable.

Cross-Species Adoption

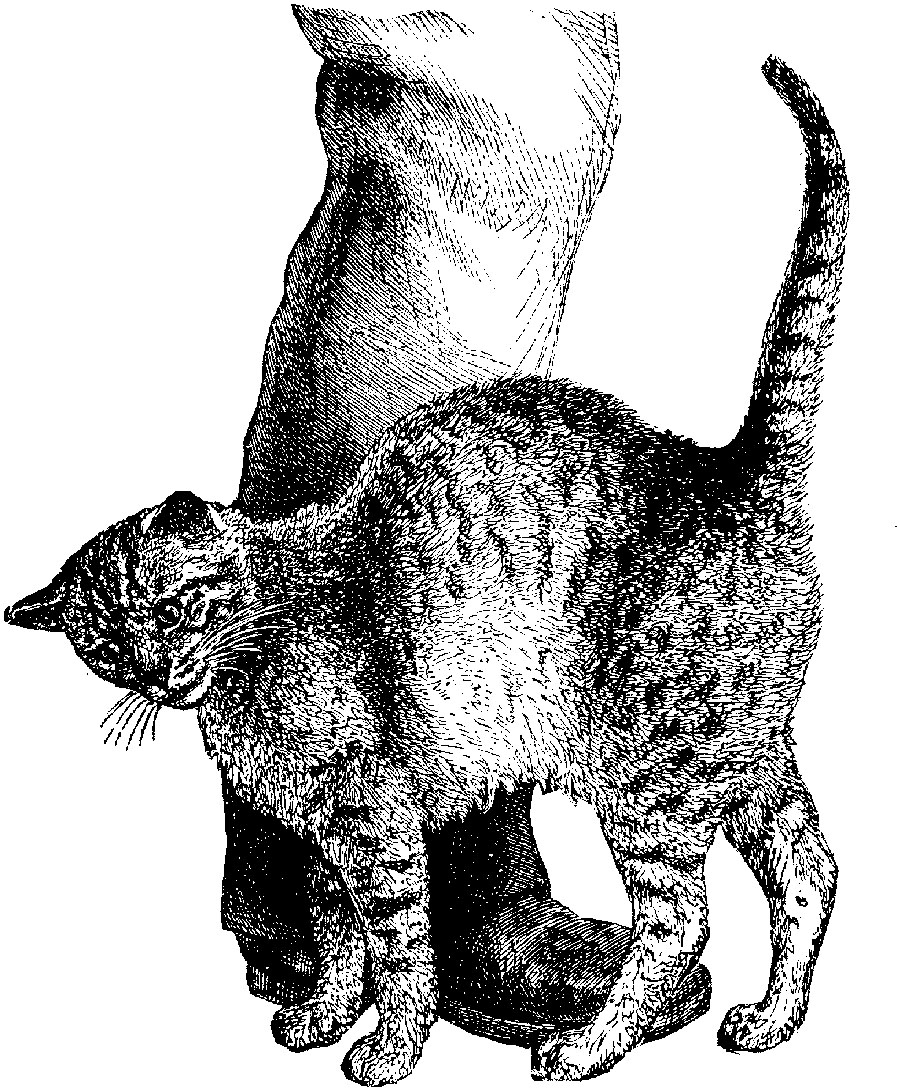

The tendency of adult animals to be nurturant toward babyish-looking animals might help explain why animals sometimes adopt the young of different species. This could be called cross-species adoption. For example, consider the following picture.

Boots the cat adopted bunnies found in the family's yard (photo by Odette Rauch-Auerbach, used by permission)

How could such a thing happen? Boots came from a humane society shelter with several kittens. They had just been given away when the bunnies were discovered in the yard.

The cat responded to the cuteness of the baby bunnies. Mothering instincts overcame predatory instincts.

Why did Boots adopt the bunnies?

Such examples were once rare. Now they are common, thanks to social media.

People tend to be delighted by cross-species adoption and enjoy sharing pictures and videos about it. This, in itself, shows the instinctive response of humans to babyishness and loving kindness between different species.

What is the benefit for the animal who does the mothering? The explanation may be similar to what Manning said about responses to supernormal stimuli.

It is better to respond mercifully to a few babies of a different species than to be insensitive to babyish stimuli. False positives are not as costly as the absence of strong parenting instincts might be.

What is a likely explanation of cross-species adoption?

As a rule, animals raised together in human households, villages, or farms learn to get along together. This is true even if their wild relatives would be in a predator/prey relationships.

Chickens, dogs, cats, goats, and guinea pigs (among other species) commonly run wild in rural villages, where they are all cared for by humans. Farms in many countries feature a variety of birds and mammals interacting peacefully.

The Animal Planet "Growing Up" series aired between 2002 to 2008. Each episode focused on a baby from a wild species raised by human foster parents. The babies' mothers had been killed, or the natural mothers rejected them.

Once the needy babies were placed with human caretakers, the outcome was always the same. Even notoriously ill-tempered species like zebras and hyenas bonded with their human adoptive parents. They responded to love.

It was also predictable that the human parents would shed a few tears when it was time for their grown-up charges to be released back into the wild. They approved of the release process, which they knew was coming all along, but they hated to see their non-human children go.

What pattern was displayed every time on the "Growing Up..." series?

Apparently bonding between humans and the young of different species is not extraordinary. It is the rule, providing humans have played a parental role during a baby animal's upbringing.

The opposite–human babies raised by non-human animals–has never occurred. Nevertheless, it is a common theme in myth (e.g. Tarzan, or the founders of Rome, Romulus and Remus, raised by a She-wolf).

Vacuum, Displacement, and Redirected Activities

We have seen how action patterns are frequently triggered by highly specific stimuli, which ethologists called sign stimuli or releasers. However, action patterns can appear without a sign stimulus.

Vacuum activity is the name Lorenz gave to behaviors set off for no apparent reason, "in a vacuum." Lorenz suggested that animals have a need to exercise biologically built-in behaviors, even if the behavior has no function.

For example, Lorenz kept a fly-catching bird as an indoor pet. Sometimes he let the bird fly around the room for exercise.

He noticed that, although there were no insects present, the bird snapped at imaginary insects in the air. There was no reason to do so; the bird was just exercising its instinctive action pattern. Lorenz called this a vacuum activity.

What is a vacuum activity?

Similarly, squirrels raised from birth in a metal cage will go through the entire sequence of nut-burying activities. Despite a lack of dirt on the floor of a metal cage, the squirrel scratches rapidly on the floor, digs an imaginary hole, takes its imaginary nut, and buries it in the imaginary hole, patting the metal floor afterward as if pushing dirt and leaves over a buried nut.

Displacement activities, as described by Lorenz, are motor programs that seem to discharge tension or anxiety. If one is offering a nut to a wild squirrel, the squirrel becomes conflicted, caught between two incompatible drives. It wants the nut, but it fears the human.

Caught between approach and avoidance tendencies, the squirrel becomes visibly nervous. It may take a few hops toward the human holding the nut, then scratch itself suddenly or make a few digging movements.

This does not mean the squirrel itches or needs to dig a hole. Lorenz suggested these displacement activities are for breaking the tension caused by competing urges.

What is displacement activity?

Humans perform displacement activities. In one study, hidden video cameras recorded nervous behaviors of people in a dentist's waiting room.

People showed all sorts of displacement activities. They scratched their heads, stroked non-existent beards, wrung their hands, tugged at earlobes, flipped through magazines at a page per second, and so forth.

People waiting for X-rays or teeth cleaning showed fewer of these activities. Like the squirrels approaching a human holding a nut, patients waiting to have cavities filled were caught between two contradictory impulses. They wanted to get the cavities filled, but they probably wanted to leave, also. So they performed nervous activities.

What are examples of displacement activities in humans? What research took place in the waiting room of a dentist's office?

Redirected activity is a third example of action patterns aroused in unusual circumstances. Lorenz defined a redirected activity as a behavior that is moved from a threatening or inaccessible target to another target that is more convenient or less threatening.

For example, flocks of chickens form a pecking order. Chickens form a rigid dominance hierarchy based on status differences respected by all members of the group.

In a chicken coop, each chicken has some other chickens it can peck (because they are less dominant). Some it cannot peck (because they are more dominant, usually larger).

At the top of the hierarchy is a chicken that can peck all the others but gets pecked by nobody. At the bottom of the pecking order is a chicken that gets pecked by all the others.

If a medium-status chicken gets pecked by a higher-status chicken, it will not fight back. It will redirect its aggression toward a lower-status chicken instead.

What is redirected activity?

Redirected activity can occur in human organizations when higher ups are disciplined by their superiors but cannot respond in kind, so they take it out on their subordinates. One student wrote:

I was in the Marines for four years and in this time I noticed the pecking order in humans all the time.

I was a sergeant and one week we had company inspection all that week. For some reason our colonel was in a real bad mood. This meant that our major would get chewed out and then the captains.

And then the captain would chew out the lieutenants and the lieutenants would chew out the gunnery sergeant and then it would get down to me. And like everyone else I made it rough on my corporals and it just would go right on down the line where the lowest one in rank would be in real trouble.

This happened all the time, because if one person wasn't in a bad mood, someone else would get that way before the day was finished. So, in the military, the pecking order is almost a daily happening. "Everything rolls downhill" (they actually used a cruder term) and like a snowball it gets bigger closer to the bottom. [Author's files]

A different form of redirected activity played a role in American comparative psychology. E.R. Guthrie was studying trial-and-error learning of a cat in a puzzle-box.

Guthrie required the cat to push against a wooden pole in the middle of the box. When the cat pressed the pole, a glass door on the front of the cage swung open, and the cat escaped.

In a 1946 book, Guthrie interpreted this as an act of learning based on the Thorndike's Law of Effect. As Moore and Stuttard (1979) note:

The animals' responses were described as highly stereotyped. A long series of movements was repeated "in remarkable detail" from trial to trial.

How did Guthrie's cat show redirected activity?

Each experimental session began with the cat being placed in the cage, while Guthrie, Horton, and "as many as eight guests sat in front of the glass-fronted chamber, unconcealed by any blind."

Pictures from Guthrie's article show the cat rubbing on the pole in the middle of the cage. It was obvious to Moore and Stuttard (1979) that the cat was greeting its visitors.

Rubbing is a cat's stereotyped greeting behavior. Because the humans were not physically available for rubbing, the cat redirected its motor program to the pole in the cage.

You can see the same thing in any friendly pet cat. It will rub not only your ankles but also nearby furniture.

A behavior similar to what Guthrie observed in the puzzle-box

Times change and perceptions change with them. What comparative psychologists of the 1940s saw as trial-and-error learning animal behaviorists of the late 1970s recognized as a species-typical behavior. It was redirected in the manner described by Lorenz. Comparative psychologists had adopted the concepts of the ethologists.

---------------------

References:

Bermant, G. & Alcock, J. (1973) Perspectives on Animal Behavior. Glenview, Il: Scott, Foresman.

Manning, A. (1972) An Introduction to Animal Behavior. Boston: Addison-Wesley.

Moore, B. R. & Stuttard, S. (1979). Dr. Guthrie and felis domesticus or: tripping over. Science, 205, 1031-1033.

Write to Dr. Dewey at psywww@gmail.com.

Don't see what you need? Psych Web has over 1,000 pages, so it may be elsewhere on the site. Do a site-specific Google search using the box below.