Copyright © 2007-2018 Russ Dewey

Adolescence

As recently as the Middle Ages, teenagers were considered adults as soon as they reached sexual maturity. Then they became eligible for marriage. For example, in Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, Juliet was 13 years old.

What are secondary sex characteristics?

The biological changes of adolescence are triggered by sex hormones. The changes brought about by sex hormones are known collectively as secondary sex characteristics: appearance of body hair, breast development in females, muscle development in males, and enlargement of the voice box producing a deeper voice in males.

What behavior is correlated with high testosterone levels in teenage boys?

Hormones also have behavioral effects. The male hormone, testosterone, causes increased aggression in all primate species. In humans, high testosterone levels correlate with "rebelliousness, talking back or fighting with classmates" (Howard, 1985).

This might explain the rebelliousness of adolescent boys in some cases. However, research shows the stereotype of rebellious adolescents is somewhat misleading.

In both males and females, hormonal changes of adolescence can lead to sudden mood changes. Rapidly changing bodies and acne can cause anxiety. According to stereotypes, adolescence is full of discord, trouble with parents, and rebellion. Carl Jung referred to adolescence as "the unbearable stage."

Rebellious teenagers tend to receive attention out of proportion to their numbers in the population. Every new rebellious type seems fascinating and threatening to older adults, and this goes back at least to the 1800s, continuing into the 20th and 21st Centuries.

In the 1950s it was ducktailed greasers playing chicken with hot-rod cars in the 1950s. In the 1960s it was flower-adorned hippies. In the late 1970s and early 1980s it was punks and New Wavers. In the 1990s it was grunge or gangsta rappers. Whatever is new and different gets media attention, even if relatively few teenagers actually fit the stereotypes.

Who gets the media attention, among adolescents?

Joseph Adelson, editor of the Handbook of Adolescent Psychology (1980) tried to set the record straight during an interview for Michigan Today. That publication discusses research by University of Michigan professors.

Interviewer: You've been studying adolescence for some time now. Have you reached any conclusions?

What did Joseph Adelson discover about adolescents?

Adelson: Only that the prevailing view of the adolescent is wrong, has always been wrong and in all likelihood will continue to be wrong.

Interviewer: That's a sweeping statement. How did you reach that conclusion?

Adelson: Some years ago I took part in a large national study, done right here at the Institute for Social Research, on the psychology of adolescence. Three thousand youngsters were carefully sampled; it was the first study of its kind, and still one of only a handful available.

...What all of us believed about the adolescent period simply was not true. Taken as a whole, they were not rebellious, nor were they impulsive, nor were they discernibly disturbed.

They were not at odds with their parents, or with society or with man's wretched destiny on this earth. They were not Holden Caulfields, nor were they James Deans–the prototypic adolescent figures of the time.

Thereupon I sought to make these findings known, published a paper reporting them and, in my blessed innocence, sat back and waited for the data to carry the day, for truth to supplant error. That did not happen then, nor has it yet.

...The idea of adolescent upheaval and alienation and defiance is a wild exaggeration. But the truth has not had much effect. ("Adolescence," 1985)

Around the same time Adelson wrote, in the mid-1980s, an eight-year study of 300 teenagers by Francis Ianni of Teachers College of Columbia University compared teens in urban, suburban, and rural environments. They found teenagers had attitudes more like parents than peers. However, there were big differences between urban, suburban, and rural teens.

Big city teenagers were most likely to reject the values of larger society and identify instead with the rules of a gang or teen subculture. Some of these teenagers seemed destined to cause conflict with society later in life, according to Ianni.

In "middle class suburban settings" the stresses and problems were of a different nature. Suburban adolescents were less rebellious and more competitive. "The situation can be highly competitive, focusing on the quest for grades or athletic achievement," Dr. Ianni said. "The casualties, then, are kids who can't compete." (Collins, 1984)

What was revealed by an eight-year study of teens? How did city, suburban, and rural teens differ?

In country settings, teenage life most often centered on "home, school and church." The most common problem among rural adolescents was a sense of "isolation and withdrawal."

Teenagers in these areas often expressed an intention to "get away" after high school. They saw few economic opportunities in their home towns, and only a few had plans to continue a family farm or business.

Changing Patterns of Young Adulthood

For research that is over 30 years old, the results above sound fairly up-to-date. If the same findings were reported this year, nobody would be surprised. However, one new influence on teenagers today is relatively new.

The iPhone was introduced by Steve Jobs at a MacWorld Conference and Expo in 2007. Within a few years, every student on a college campus was walking around with a gadget held to the ear.

This quickly filtered down to younger teenagers. By 2011, 36% of teens had a smartphone. One year later it was 58%. By 2015 the number was 73%.

Most media reports of this phenomenon are negative. The teenagers were at it again, doing strange new things to threaten society. The typical article about teenagers and smartphones concentrated on warnings:

Smartphones were causing "addiction" (because teenagers like to use them a lot).

Smartphones were causing fatalities if people text while driving (true).

Smartphones were causing sleep loss (because teenagers could communicate with friends at night).

Smartphones were causing stress, anxiety, and tendonitis from all that tapping.

Smartphones were opening the door to cyberbullying and sexual exploitation.

Smartphones were a huge distraction in class and were used for cheating (true if teachers do not intervene).

Increased screen time "neglects the circuits in the brain that control more traditional methods for learning...

A few (rare!) articles tried to present counterbalancing benefits.

Teenagers could share pictures and ideas with friends and family, even when on a fieldtrip.

Smartphone users had access to online tutorials about every subject.

Smartphone users showed better coordination and problem solving skills.

The usual recommendation, after listing dangers, was to limit teenagers' access to smartphones to an hour or two per day. Keep smartphones out of bedrooms. Allow smartphone use as an occasional treat.

Nobody gave the best advice of all: avoid parenting sites with exaggerated warnings. Celebrate your kid's intelligence and enthusiasm. Learn from their willingness to embrace technological change, given that it is pervasive and unavoidable in the modern world. (But those are just my opinions, not based on research.)

If statistical trends are to be trusted, smartphones are not having a bad impact on adolescents in the United States or other countries. Teen pregnancies are down, college application rates are up, political awareness is on the increase, and rebellious teenage subcultures seem to have disappeared from the media landscape for the first time in decades.

Richtel (2017) noted an encouraging trend: "American teenagers are growing less likely to try or regularly use drugs, including alcohol." He wrote:

Researchers are starting to ponder an intriguing question: Are teenagers using drugs less in part because they are constantly stimulated and entertained by their computers and phones?

The possibility is worth exploring, they say, because use of smartphones and tablets has exploded over the same period that drug use has declined. This correlation does not mean that one phenomenon is causing the other, but scientists say interactive media appears to play to similar impulses as drug experimentation, including sensation-seeking and the desire for independence.

Or it might be that gadgets simply absorb a lot of time that could be used for other pursuits, including partying (Richtel, 2017).

Meanwhile, nearly every teenager is competent using a handheld computer. They know how to access the accumulated knowledge of humanity, and they are mostly self-taught in these skills.

It is not just teenagers. Yesterday (when I first wrote this) my wife and I arrived at the Savannah International Airport to wait for our son, flying in from Tokyo for a spring visit. I brought a smartphone, hoping the airport had free WiFi.

A maintenance man was riding by on a mobile vacuum cleaner. I waved to him and he stopped, and I asked if there was WiFi at the airport.

He said it was offline earlier but he would check, and he whipped out a smart-looking LG smartphone, tapped a few keys, and said Yes, it was available; just log on to FlySAV and if it asks you for a password, don't bother, it will connect automatically.

I logged on and spent the next twenty minutes reading news until our son's plane arrived. I couldn't help thinking how remarkable that encounter would have seemed 20 or 30 years earlier.

It made me ponder how the world had changed. Even dinner conversations are different, because when somebody wonders aloud about some factual matter (just about anything) somebody else will say, "I'll check" and a few seconds later they have the answer.

Why would this NOT have an impact on young people growing up in our society? Young people are at the forefront, because they are growing up with these gadgets and take them for granted. Older adults are the only ones intimidated by this technology. Most young people have mastered it.

The Questing Stage

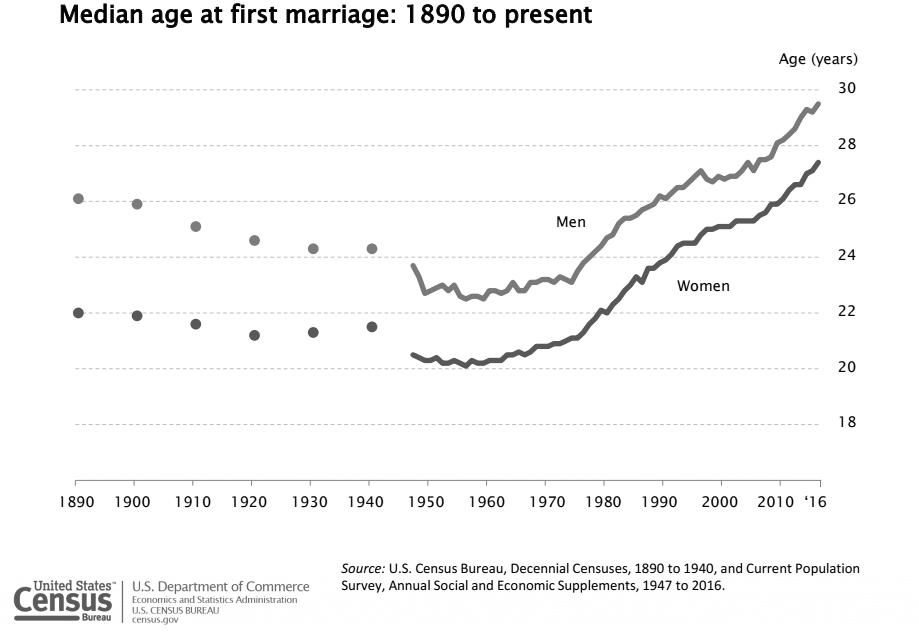

One pronounced change in patterns of young adulthood in recent decades is age of first marriage. The graphic below, from the U.S. Department of Census, shows males (top line) and females (bottom line) both approaching 30 years old for the average age of first marriage.

The average age of first marriage is approaching 30 years old in the U.S. (shown) and also in Europe.

No longer do young people automatically marry after graduating from high school, or even after graduating from college. Instead, there is a new developmental phase between adolescence and adulthood, according to New York Times columnist David Brooks:

There used to be four common life phases: childhood, adolescence, adulthood and old age. Now, there are at least six: childhood, adolescence, odyssey, adulthood, active retirement and old age. Of the new ones, the least understood is odyssey, the decade of wandering that frequently occurs between adolescence and adulthood. (Brooks, 2007)

Finder (2005) also noticed the trend:

"Laurie Heckman worked as a whitewater rafting guide in Colorado. Steve Wiener has been crisscrossing the country in a large van, taking international tourists to see major cities and national parks. Zach Carson bought a small bus, converted the engine to run on recycled vegetable oil and is touring the country promoting alternative fuels.

"All are recent college graduates who intend to go on to graduate school, but not yet. Like a growing number of graduates, they are taking time away from school and the vigorous pursuit of a career.

"Some are looking for new experiences; others want to test potential careers or devote themselves to public service for a while; still others simply want to have a good time after the rigors of high school and college."

Henig (2010) wrote, in an article titled, "What is it about 20 somethings?":

"The 20s are a black box, and there is a lot of churning in there. One-third of people in their 20s move to a new residence every year. Forty percent move back home with their parents at least once.

"They go through an average of seven jobs in their 20s, more job changes than in any other stretch. Two-thirds spend at least some time living with a romantic partner without being married. And marriage occurs later than ever...

"We're in the thick of what one sociologist calls 'the changing timetable for adulthood.'"

---------------------

References:

Adolescence. (1985, December). Adolescence. Michigan Today, p. 6-7.

Adelson, Joseph (Ed).(1980) Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. New York: Wiley.

Brooks, D. (2007, October 9). The Odyssey Years. New York Times Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.

Collins, G. (1984, February 6). Study says teenagers adopt adult values. New York Times, p.20.

Henig, R.M. (2010, August 18) What is it about 20-somethings? New York Times Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.

Howard, C. (1985, November). Passage through puberty. Psychology Today, p.20.

Kohn, A (1984, July). Teenagers under glass. Psychology Today, p.6.

Richtel, M. (2017, March 13) Are teenagers replacing drugs with smartphones? New York Times. Retrieved from: https://www .nytimes.com/

Write to Dr. Dewey at psywww@gmail.com.

Don't see what you need? Psych Web has over 1,000 pages, so it may be elsewhere on the site. Do a site-specific Google search using the box below.