Copyright © 2007-2018 Russ Dewey

Conformity

Conformity is likeness or similarity of behavior and appearance. A conformist is one who tries to be the same as everyone else.

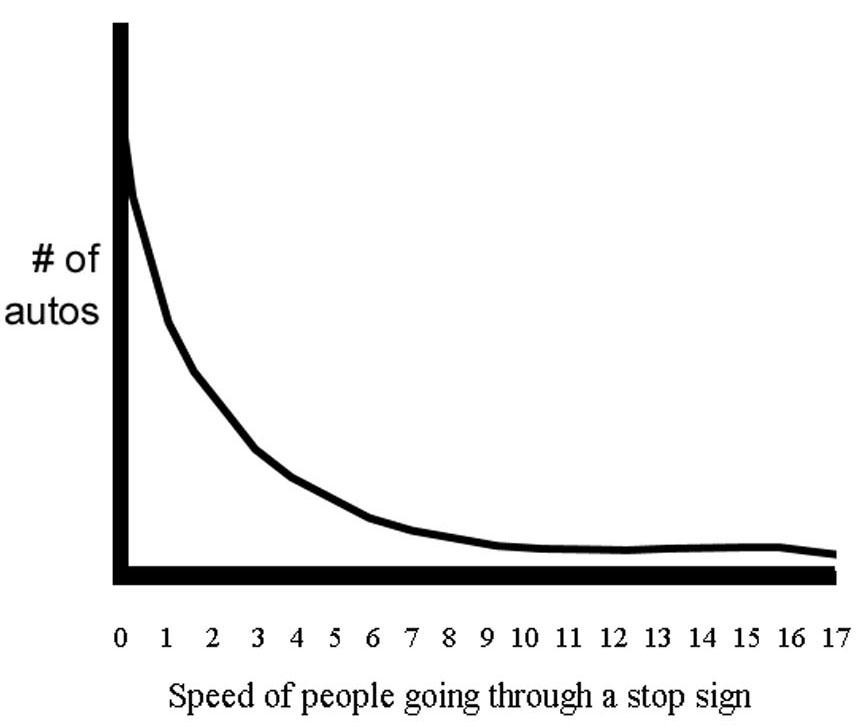

In 1934, Floyd Allport (brother of Gordon Allport, the personality theorist) pointed out that conformity followed a regular pattern. In a publication titled, "The J-curve hypothesis of conforming behavior" (1935), Allport suggested that small deviations from social rules are common, while larger deviations are increasingly rare.

What pattern was shown by Floyd Allport's J-curve of conformity?

For example, consider the speed of motorists going through a stop sign. The law says everybody should come to a full stop at a stop sign.

In reality, many people "slide through" (which can earn them a ticket). Some people–comparatively few–drive through at higher speeds.

Floyd Allport's J-curve of conformity

If the data is put on a graph, it looks like a J-shaped curve (log curve). The higher the speed (the greater the non-conformity) the more rare is the event.

Sherif (1935): Conformity and Group Norms

Muzafer Sherif conducted a classic study on conformity in 1935. Sherif put subjects in a dark room and told them to watch a pinpoint of light and say how far it moved.

Psychologists had previously discovered a small, unmoving light in a dark room would appear to be moving. This was labeled the autokinetic effect.

The autokinetic effect is an illusion; the light does not actually move. However, people usually believe that it does.

How did Sherif use the autokinetic effect to study conformity?

Sherif realized an experience completely "in people's heads" might be influenced by suggestion. He decided to study how the autokinetic effect might be influenced by other people's opinions.

First Sherif studied how people reacted to the autokinetic effect when they were alone in the room. He found that individuals established a norm for the judgment. They usually deciding the light was moving between 2 to 6 inches, and they became consistent in making this judgment from trial to trial.

Next groups of subjects were put in the dark room, 2 or 3 at a time, and asked to agree on a judgment. Now Sherif noted a tendency to compromise.

People who usually made an estimate like 6 inches started to make smaller judgments like 4 inches. Those who saw less movement, such as 2 inches, soon increased their judgments to about 4 inches. People changed to resemble others in the group.

Sherif's subjects were not aware of this social influence. When Sherif asked subjects, "Were you influenced by the judgments of other persons during the experiments?" most denied it.

What happened when people judged the autokinetic effect by themselves? In groups?

However, when subjects were tested one at a time, later, most now conformed to the group judgment. A subject who previously settled on an estimate of 2 inches or 6 inches was more likely (after the group experience) to say the light was moving about 4 inches.

These subjects were changed by the group experience, whether they realized it or not. They had increased their conformity to group norms or agreed-upon standards of behavior.

Sherif's experiment showed that group norms are established through interaction of individuals, with a leveling-off of extreme opinions. The result is a consensus agreement that tends to be a compromise, even if it is wrong.

Asch (1951): Conformity

Perhaps the most influential study of conformity came from Solomon E. Asch (1951). Asch gave groups of seven or nine college students what appeared to be a test of perceptual judgment.

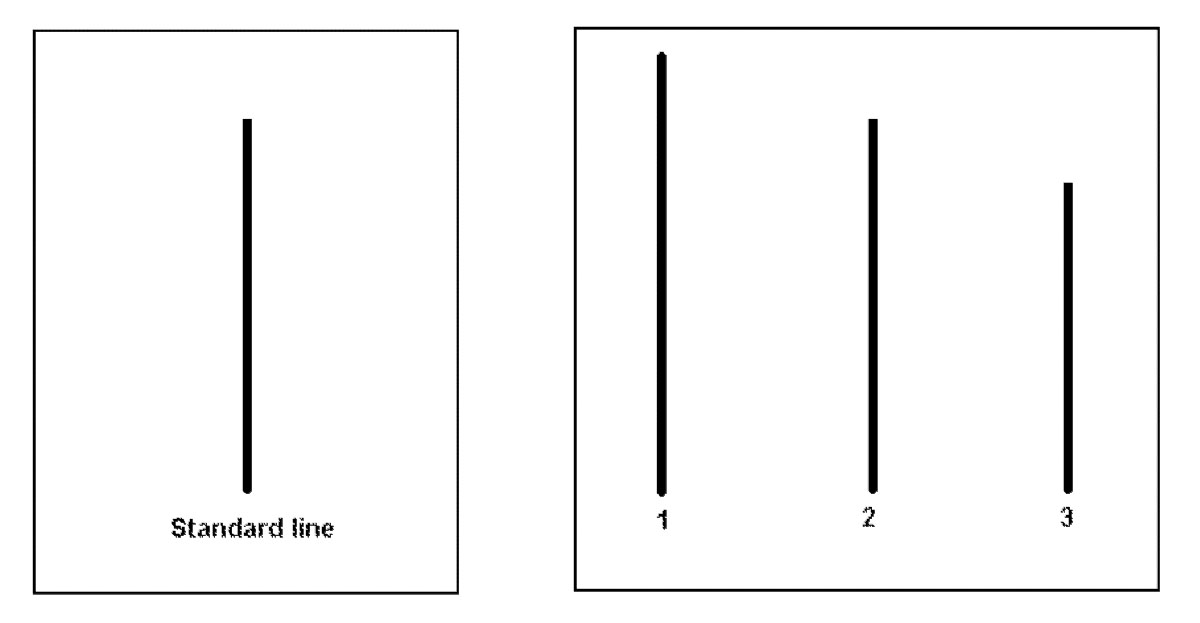

Participants had to match the length of a line segment to comparison lines. Each subject saw a pair of cards set up in front of the room, similar to the ones below.

Stimuli like those used by Asch

Participants received the following instructions:

This is a task involving the discrimination of lengths of lines. Before you is a pair of cards. On the left is a card with one line. The card at the right has three lines different in length; they are numbered 1,2, and 3, in order.

One of the three lines at the right is equal to the standard line at the left. You will decide in each case which is the equal line. You will state your judgment in terms of the number of the line.

There will be 18 such comparisons in all... As the number of comparisons is few and the group small, I will call upon each of you in turn to announce your judgments.

In a group of nine, eight subjects were actually confederates of the experimenter. The experiment was rigged so that the genuine (naÏve) subject was always the next-to-last to be called upon.

The experimenter's confederates were instructed, in advance, to make deliberately ridiculous judgments on many trials, but to agree unanimously with one another. On 12 of the 18 trials, they said in loud voices (for example) that the 4 1/2" line was equal to 3" standard line.

The pressure of the group had a dramatic effect. Although people could pick the correct line 99% of the time when making the judgments by themselves, when they were put into the group of nine, 75% went along with an obviously incorrect group judgment at least once.

Asch's data can also be used to argue that people were nonconforming, most of the time. Adding up all the data, people under pressure to conform gave correct responses 63% of the time.

Despite the fact that only a third of the responses from naÏve subjects showed the conformity effect, Asch's experiment was interpreted as showing powerful pressures toward conformity. Most people found it remarkable that subjects could be induced to give an obviously wrong judgment a third of the time.

How did Asch's subjects rationalize making obviously wrong judgments?

The conforming subjects did not fool themselves into thinking the wrong line was equal to the standard line. They could see the difference. However, they were influenced by seven people in a row making the "wrong" decision.

Asked later why they had made such obviously incorrect judgments, subjects reported, "They must have been looking at line widths" or "I assumed it was an optical illusion" or "If eight out of nine people made the same choice, I must have missed something in the instructions."

Asch obtained the conformity effect even when the confederate declared an eleven-inch line to be equivalent to a four-inch standard. He found that small groups, even groups of three with two confederates and one naÏve subject, were sufficient to induce the effect.

How many subjects remained independent and did not conform?

About a quarter of the subjects remained independent throughout the testing and never changed their judgments to fit those of the group. Asch's experiment showed stubborn independence in some people, just as it showed conformity in others. A subject who did not conform reported to Asch later:

I've never had any feeling that there was any virtue in being like others. I'm used to being different. I often come out well by being different. I don't like easy group opinions.

Asch later tested the effect of having a dissenter in the group. He found that if only one of seven confederates disagreed with the group decision, this was enough to free most subjects from the conformity effect.

However, if the dissenter defected later, joining the majority after the first five trials, rates of conformity increased again. The public nature of the judgment also seemed to have an effect. If subjects were invited to write their responses in private, while the majority made oral responses, this destroyed the conformity effect.

What happened when there was a dissenter in the group? If responses were written in private?

Asch's experiment inspired follow-up research by other experimenters. The following factors increased conformity:

1. Attractiveness of other members in the group (people tended to go along with a group of attractive people)

2. Complexity or difficulty of the task (people were more likely to conform if the judgment was difficult).

3. Group cohesiveness (people conformed more if friendships or mutual dependencies were set up beforehand).

What factors increased conformity?

How do we explain the power of the pressure to conform? Ross, Bierbauer, and Hoffman (1976) point out that the conformity situation may have been more pressure-packed than most people appreciate.

To appreciate further the nature of this dilemma, let us imagine an introductory lecture in psychology. The instructor is describing the Asch study and has just shown a picture of the experimental stimuli.

Suddenly he is interrupted by a student who remarks, "But line A is the correct answer..." Predictably, the class would laugh aloud and thereby communicate their enjoyment of their peer's joke.

Suppose, however, that the dissenter failed to smile. Suppose, instead, he responded, "Why are you all laughing at me? I can see perfectly, and line A is correct."

Once convinced of the dissenter's sincerity, the class response almost certainly would be a mixture of discomfort, bewilderment, concern, and doubt about the dissenter's mental and perceptual competence. It is this response that the Asch dissenters risked and, accordingly, it is not surprising that many chose to avoid it through conformity. (Ross, Bierbauer, and Hoffman, 1976)

Was the Asch conformity effect due to the era in which it was carried out? After all, the early 1950s were famous for emphasizing conformity, such as the "corporate man" who did everything possible to eliminate his individuality and fit into a business setting.

To see if the same experiment would work with a later generation of subjects, NBC news had social psychologist Anthony Pratkanis replicate the Asch experiment in front of a hidden camera for its Dateline show in 1997.

The experiment still worked, and the percentage of conformists was almost identical to what Asch found. Even students whose appearance suggested creativity or rebellion went along with obviously incorrect group judgments. Later they explained they did not want to look foolish, so they just "caved in."

What did NBC find out, in 1997? What did a more formal survey show?

A more formal survey was conducted by Bond and Smith (1996). They found 133 replications of the Asch experiment in 17 countries. "An analysis of U.S. studies found that conformity has declined since the 1950s," they reported.

The researchers used results from 3 surveys to play each country on a dimension of individualism-collectivism. Collectivist countries (those where group action are encouraged or enforced from above) "tended to show higher levels of conformity than individualist countries."

Social Learning in Non-Human Animals

Conformity is a somewhat pejorative (insulting) term. It implies people are imitating each other for mindless or inadequate reasons. However, imitation can be adaptive in both human and non-

Allen, Weinrich, Hoppitt, and Rendell (2013) studied social learning in humpback whales. Humpback whales are known to use a technique called bubble-feeding. They blow rings of bubbles far below the surface, surrounding a school of fish they intend to eat, then lunge through the "bait ball" to feed.

In 1980 a single whale off the coast of Maine added an innovation: a tail slap on the surface, one to four times, before the bubble-feeding procedure. Perhaps this signaled other humpbacks that it was time to begin the process.

From 1981-1989 the tail-slap innovation became more common. By 2007 37% of bubble-feeding events were preceded by tail slaps. But the behavior was still confined to the Maine area. Was it perhaps due to unique conditions in that area, rather than observational learning?

The researchers used a statistical tool called network-based diffusion analysis to determine how the behavior was spreading. This tool estimated the proportion of time individuals were associated, which was possible because individual whales had GPS transmitters

If the behavior was being culturally transmitted, individuals who associated should be more likely to learn the new behavior. That was "overwhelmingly" the case. Learning rate increased in direct proportion to the time that individuals spent near each other.

How did Humpback whales imitate each other?

That is just one example of cultural transmission in non-human animals, and many more exist. Japanese macaques imitated a new habit of washing sweet potatoes, which were being brought to them as food by humans. Passerine birds learned to open milk-bottles, and this behavior eventually spread to a whole flock.

To study imitation (conformity) under controlled conditions, Waal, Borgeaud, and Whiten (2013) used food coloring on corn fed to vervet monkeys. In two groups, blue corn was made highly distasteful, in two other groups pink corn was made to taste bad. The two trays of colored corn were next to each other.

After three monthly training sessions, the bad-tasting color was rarely eaten. Now came the experimental test. After waiting for a new batch of infants who had no experience with colored corn, the two trays were set out again.

This time, both colors tasted the same, and both tasted good. However, the mothers remembered the earlier training and only ate one color. Overwhelmingly, the babies copied their mother's preference and picked only the color of corn eaten by the mother. The researchers wrote:

Just one infant's first choice was of the alternative-colored food. Its mother was of low rank and took a small amount of the nonpreferred food while higher-ranked individuals were monopolizing the preferred food. Accordingly, 27 of 27 infants first took the food they witnessed their mothers eat (for 26 of them, the one they would also see most eaten in their group). (Waal, Borgeaud, and Whiten, 2013).

This form of learning was not limited to babies imitating mothers. In a later variation, the same group of researchers showed that immigrants, vervet monkeys from other groups, adopted food preferences of the group they joined.

Researchers have documented many other examples of cultural learning in non-human animals. The phenomenon is widespread and clearly gives animals an adaptive advantage. Those capable of conforming are more likely to succeed and reproduce.

How did vervet monkeys show conformity?

In short, conformity may sound negative (and sometimes is) but social learning can be beneficial. Cultural transmission, knowledge propagation, and social learning are conformity by a different name, and in many cases they are desirable.

Conformity is convergence on a way of behaving. The opposite phenomenon is divergence. Divergence also goes by many names: non-conformity, innovation, individuality, or uniqueness. Like conformity, it can be a good or a bad thing, depending on the situation.

Hodges (2014) analyzed four different lines of research on human children. All showed both convergence and divergence in the behavior of children interacting with each other and with adults. Even young children acted like thoughtful explorers "rather than acting as if they are solo explorers or blind followers." Hodges concluded:

One of the deepest assumptions of social psychology, and many allied disciplines, is that people have strong tendencies to conform, to imitate, to mimic, and to obey. These tendencies are claimed as the basis for coordination, communication, and culture...

The available evidence, though, reveals a far more complex and interesting set of dynamics: divergence is as pervasive as convergence, but its appearance is often unnoticed or minimized.

The story that needs to be told is interweaving of convergence and divergence, Hodges suggested. Rather than focusing on individuals as conformists or dissenters, we need to tackle the way imitation and innovation are mixed. Both are necessary as creatures learn to navigate their social worlds.

---------------------

References:

Allen, J., Weinrich, M., Hoppitt, W., & Rendell, L. (2013) Network-based diffusion analysis reveals cultural transmission of lobtail feeding in humpback whales. Science, 340, 485-488. doi:10.1126/

Allport, F. (1934) The J-curve hypothesis of conforming behavior. Journal of Social Psychology, 5, 141-183.

Asch, S. E. (1951) Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgments. In H. Guetzkow (Ed). (1951). Groups, leadership and men; research in human relations. Oxford, England: Carnegie Press. (Pp. 177-190)

Bond, R. & Smith, P. B. (1996) Culture and conformity: A meta-analysis of studies using Asch's line judgment task. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 111-137. https://dx.doi.org/

Hodges, B. H. (2014) Rethinking conformity and imitation: Divergence, convergence, and social understanding. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 726. doi:10.3389/

Ross, L., Bierbrauer, G., & Hoffman, S. (1976) The role of attribution processes in conformity and dissent. American Psychologist,31,148-157. https://dx.doi.org/

Sherif, M. (1935) A study of some social factors in perception. Archives of Psychology, no. 187.

Waal, E., Borgeaud, C., & Whiten, A. (2013) Potent social learning and conformity shape a wild primate's foraging decisions. Science, 340, 483-485. doi:10.1126/

Write to Dr. Dewey at psywww@gmail.com.

Don't see what you need? Psych Web has over 1,000 pages, so it may be elsewhere on the site. Do a site-specific Google search using the box below.